Lower back pain: causes and prevention for cyclists

Although cycling is a low-impact sport, many cyclists still suffer with back pain. We take a look at why this is and what can be done

Whether it’s a dull ache that sets in towards the end of a ride, the odd twinge getting in and out of the chair at the coffee stop, or a raging sciatica that prevents cycling altogether, many of us have experienced some form of back pain. And the sad truth is, these problems often seem to be brought on – or at least exacerbated – by riding a bike.

You might be frustrated; you might be in pain; but one thing you certainly won’t be is alone. The UK Health & Safety Executive put the number of work days lost to back pain at 2.8 million in 12 months across 2018-19. More seriously, it’s not unreasonable to estimate that the number of bike rides missed runs to seven figures, or at least not far off.

Cyclists seem to get a raw deal in the back pain stakes. A Norwegian study of 116 pro cyclists found lower back pain to be the most prevalent overuse injury in the group, with 49 cyclists reporting the issue.

But as our Fitness Editor (print) David Bradford discovered from his myth-busting deep-dive into the misconceptions surrounding cycling and backpain, cycling itself is actually near the bottom of the table when it comes to documented injury-risk prevalance figures.

The way to think about it is: back pain is a common issue across the population as a whole and, as such, is also a common issue across the cycling community, too.

CAUSES OF LOWER BACK PAIN

“Number one is our lifestyle,” says Dan Boyd, a physiotherapist and bike-fitter at Complete Physio in London, when asked why cyclists are so vulnerable to injury. “Unfortunately, we spend a lot of time at a desk and we weren’t particularly designed to sit at desks, which puts a lot of strain on our thoracic [mid] and lower back. That’s pretty unavoidable for most people, certainly recently.”

The posterior chain – the muscles in your back, bum and the backs of your legs – is king. Unfortunately, these muscles get ‘switched off’ by sitting for long periods.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

DON’T BLAME YOUR BIKE SET UP FOR LOWER BACK PAIN WHEN CYCLING

Correct bike set-up can certainly help to avoid low back pain (and we'll come to that later), but in the study on elite cyclists above, they were supervised by national coaches with access to advanced facilities, so incorrect bike geometry wasn't likely to have been a factor.

What else could be going on?

Well, some research has shown that muscle fatigue may play a role. In one study, scientists demonstrated that when cyclists pedalled to exhaustion, their hamstrings (rear thigh) and calf muscles became progressively more fatigued (as expected).

What was surprising, was that this fatigue seemed to produce undesirable changes in muscle movement patterns, which then affected the back - specifically, the degree to which the cyclists were bent forward in the lumbar region and also how far their knees were splayed out.

IMPAIRED SPINAL MOVEMENT CAN CAUSE LOWER BACK PAIN IN CYCLISTS

Another study looked at the effects of holding a static bent-forward (flexion) position on the all-important back extensor muscles that help maintain stability in the lower back.

It found that after prolonged periods of static flexion (when a cyclist is on the drops), these muscles became less effective at generating the forces required to maintain spinal stability.

More evidence for this effect comes from Australian research, which compared nine healthy (symptom-free) cyclists and nine cyclists with chronic lower-back pain. In short, the researchers found that the cyclists in the pain group tended to have excessive increased lower back flexion (forward bending in the lower back), which was associated with reduced activity of deep low-back muscles called multifidus - key stabilisers of the lumbar spine.

The notion of impaired spinal-movement patterns as a major cause of lower-back pain in cyclists is also supported by Belgian research, which found that cyclists measured riding their own bikes, and who were chronic lower-back pain sufferers, tended to ride with more flexion in the lower lumbar spine. They also tended to experience a steady increase in pain over a two-hour period compared to healthy cyclists.

The scientists concluded that rather than poor bike set-up, it was the cyclists' impaired motor control patterns in the lumbar region that led to poor movement patterns, specifically excessive flexion, resulting in lower back pain.

ADJUST YOUR EXPECTATIONS WHEN DEALING WITH LOWER BACK PAIN FROM CYCLING

“The back is a crossover point in the body,” Boyd notes. “Pretty much all the forces we have travel through our back, whether it’s rotational or position-based, and also it’s the bit that holds us together.”

It sounds like a recipe for disaster, but Boyd insists: “To be fair, the back is an exceptionally well designed bit of kit, but what we ask of it is probably quite a lot, particularly through cycling... Some of the endurance events people get injured doing are pretty extreme.” As an Ironman triathlete, he speaks from experience.

The blame, Boyd says, lies not so much with our backs, but with our expectations; as the movie line goes, our egos are writing cheques our bodies can’t cash.

“The expectations of cyclists and triathletes, in my experience...” Boyd hesitates trying to find diplomatic words, “the level of normality gets somewhat distorted.”

Some of us need to view our bodies a little more sympathetically. “Cycling 100 miles is an awful lot to put on your body, but quite normal for a lot of people, particularly nowadays.”

So what if you enjoy riding long distances? If you’re a regular racer, club rider or Audax rider, rides of up to 100 miles are probably part of what you love about bike riding. Thankfully, Boyd says you don’t necessarily have to give these up to preserve back health. Much back pain seems to be preventable given a little attention, both on and off the bike.

HOW TO PREVENT LOWER BACK PAIN

SELECT THE CORRECT FRAME GEOMETRY

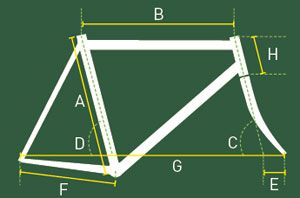

A: Seat tube length | B: Top tube length | C: Head tube angle

D: Seat tube angle | E: Fork offset | F: Rear centre

G: Wheelbase | H: Head tube length

Although lower back pain often arises as a result of weakness or improper movement as a result of fatigue, it is a good idea to assess your bike fit too as this can be a contributing factor.

This could be as simple as tweaking your current setup. Shuffling some of the spacers sitting on top of your stem down underneath it will raise up your handlebars, meaning your back won’t have to bend as severely to reach them. Equally, swapping out a long stem for a shorter one will prevent you from having to stretch out quite so far, also reducing the stresses on your spine.

If those adjustments aren’t sufficient - or if you’re looking to purchase a new bike anyway - opting for a model that best matches your flexibility will help you stay injury free. Generally, this would involve opting for an ‘endurance’ model rather than a ‘race’ model, the former of which will tend to place you in a less extreme and more relaxed position than the latter.

Remember, it’s still perfectly possible to ride hard and fast on an endurance bike, should you wish. Trek’s Domane endurance bike has titles at Paris-Roubaix - as does Specialized’s Roubaix endurance bike. A comfortable and sustainable position that allows you to put the power out will see a better performance than overreaching with too aggressive a geometry.

Getting a professional bike fit will help ensure that you’re riding in an optimum position - and getting your fit data before pulling the trigger on any purchases would make a very wise decision.

OPTIMISE YOUR BIKE SET-UP TO MINIMISE INJURY RISK

If you're happy that you're sitting aboard a frame with geometry that suits you, you need to get set up on it correctly. Here's a look at the key elements to look at:

Saddle height: This should be positioned so that when the pedal is at the bottom of the stroke and the ball of your foot is on the pedal, your knee should have a slight bend in it. Hips shouldn't move sideways during crank rotation and you shouldn't have to stretch at the bottom of the pedal stroke.

Saddle angle: This should be in a horizontal position, parallel with the floor when viewed side on (but sometimes a very slight downwards tilt can be helpful for those who experience a lot of pressure in the perineum area).

Forwards/backwards position of the saddle: With the pedals adjusted so that they are at the three o'clock and nine o'clock positions, a vertical line dropped from just behind the kneecap on the outside of the forward knee should pass through the axle of the pedal.

Handlebar position: Handlebars should be adjusted so that you neither have to stretch to reach them, or feel confined by having them too close to your body. You should be able to comfortably reach the bars from an upright position and your elbows should be slightly bent when resting on them.

In addition, it’s also good to make sure that your gearing matches the demands of the terrain. Keeping the cranks spinning using a lower gear - rather than loading your muscles and joints with excessive force when stuck in one too big - will help to reduce the chance of injury.

A local bike shop or bike fitter will be able to give you more specific advice for the terrain around you. But in general, 50/34 tooth chainrings and an 11-32 tooth cassette will provide a good range for most people in most places.

When it comes to pedals that you clip in to, proper cleat set up is vital to make sure that you’re not putting yourself through injury-inducing stresses. On the flipside, once you have got your cleats set up, spinning the cranks takes very little thought or coordination as your feet are fixed in place, which reduces the risk of injury.

WHAT DO YOU DO IF YOU DO FIND YOURSELF TROUBLED BY LOWER BACK PAIN?

SHOULD YOU SEEK MEDICAL HELP?

The NHS UK website states that most back pain is not serious and usually gets better over time, and suggests keeping active, taking ibuprofen if it’s safe for you to do so, and trying hot or cold packs. It adds that if it doesn’t start to improve within a few weeks, stops you from doing day to day things, or is severe, “it’s a good idea to get help.”

A GP can refer you to a physiotherapist or musculoskeletal consultant or, in order to be seen straight away, you can opt to go privately to a physio, chiropractor (not widely endorsed by the NHS) or osteopath. If at this point you are diagnosed with a disc problem, be prepared to make two new friends: patience and light exercise.

“Unfortunately, once we know it’s a disc or a nerve impingement, you’re coming off the bike,” Boyd says, “because they’re very difficult to manage during sport.”

Out with cycling, then, but in with lighter forms of exercise.

“‘Activity modification’ is the phrase used in the literature,” Boyd continues. “Walking certainly is one of the best things you can do for back pain. So keeping active sensibly, I think – basically limiting impact exercise and not putting too much load… usually guided by someone who’s had a look at your scans and whatever pathology you’ve got.”

In the case of Cycling Weekly’s James Shrubsall – at least in his most recent episode – “it was regular sessions with a physiotherapist that put me back on track,” Shurbsall said. “She helped me mobilise my spine and ironed out some of the tension in my lower back muscles. Things quickly dialled down from ‘very bad’ to simply ‘bad’ on the ‘How messed up is my back-o-meter’, which I was eternally grateful for. (It’s worth adding that in the past I have had good results with both a chiropractor and an osteopath).

“It was around this point, after nearly four months off the bike, that I first turned the pedals again: six minutes on Zwift averaging 85 watts. But it was a start. Six weeks later, I was up to an hour outside, but that proved a bridge too far and necessitated a further month off the bike.”

As Boyd says: “It’s about expectation alteration. When someone’s expectation is not aligned with the underlying physiology [of the issue], that’s where it goes wrong.”

Thankfully, more small steps, more physio, daily stretching and a good deal of core work saw Shurbsall build back up to the 60-mile benchmark, with painkillers becoming a thing of the past - bar the occasional paracetamol.

The last key healer in the equation has undoubtedly been time. Sadly, without going under the knife (and even that is no guarantee), nerve and disc issues like sciatica require patience.

"I’m still waiting for it to resolve itself completely," Shurbsall admitted, "but as it’s still improving, I’m confident that one day I’ll be pain-free. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have some core exercises to do..."

There are many different types of back pain but the headlines are ‘muscles’ and ‘discs’.

Muscles can suffer as a result of going a bit too far or hard on the bike, or even lifting something too heavy, leaving you nursing a strain. Strains can cause painful spasms, your body’s way of ‘freezing’ your back to stop you doing any more damage, and can take weeks to heal. The good news, as Boyd says, is that exercise and movement can help the healing process.

Discs issues, as we have seen, are extremely common – though many such cases involve no pain, and the effects are difficult to predict. The classic cause of pain is a damaged disc that bulges outwards from the spinal column (a so-called slipped disc) and impedes the sciatic nerve, resulting in pain, often down the leg, that can vary from mild to severe. Disc issues can also cause spasming.

Sadly, other common injuries and niggles for cyclists include knee pain and wrist pain - but on a more positive note, we've got advice on how to overcome those issues too. You can pop over onto those pages to read all about it.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

- David BradfordFitness editor

- Anna Marie AbramFitness Features Editor

- James Shrubsall

-

Nightmares, niceties and gnarl: 10 years of the Transcontinental Race

Nightmares, niceties and gnarl: 10 years of the Transcontinental RaceThe ultra-distance benchmark that pits riders against a 4,000km self-supported Europe-wide trek reaches double figures

By James Shrubsall Published

-

Why the best commute will always be aboard my old steel fixie

Why the best commute will always be aboard my old steel fixieCharming, simple, and always a great workout, this is the perfect town bike

By Joe Baker Published