Can you buy your way to a fitter you?

As cyclists we’re endlessly enticed by brands promising that their products will make us fitter and faster if only we shell out some cash. How to sort fact from falsehood? Dr Nick Tiller assesses the evidence behind some of cycling’s most popular ergogenic aids

Whether you’re a weekend warrior or a pro cyclist, achieving your cycling goals requires endless dedication and many hours in the saddle.

We naturally seek out shortcuts and are drawn to the magnetic allure of the ergogenic aid — external influences and products that claim to enhance performance.

Ergogenics range from supplements and drugs (nutritional aids), imagery and self-help (psychological aids), to training programmes and simulated altitude (physiological aids).

But which ones really work?

In the world of sports consumerism, we’re forever exposed to flashy ad campaigns and marketing rhetoric designed to extract from us our hard-earned cash.

The products we’re sold, disguised as magical elixirs, promise greater health and performance, often making claims as broad as they are bold — but often weakly substantiated by the evidence. It’s time to sort the facts from the fads.

Altitude training

The 1968 Mexico Olympic Games exemplified the potential for altitude to impact on performance. Athletes who resided or trained at altitude dramatically outperformed the unacclimated lowlanders.

These days, altitude training is common practice among the elite; Team Sky, among others, regularly spend time training on Tenerife, sleeping at 2,500m on the slopes of Mount Tiede.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

However, despite many decades of research, there are many unknowns and disadvantages.

>>> Watch: Your guide to the perfect training camp

Endurance performance is largely determined by your body’s ability to drive oxygen from the atmosphere into the exercising muscles. Altitude of above 2,000m induces your muscles into hypoxia — low oxygen concentration — stimulating a cascade of adaptations, boosting red blood cell production, which improves oxygen delivery.

The most effective strategy appears to be ‘live high, train low’, whereby athletes live for an extended period of time at altitude but train in normal conditions using artificial gas mixtures.

Learn more about VO2 max

However, there are many drawbacks to traditional altitude training, often overlooked by the media, which may make you think twice before heading for the hills.

First, many of the benefits of an altitude sojourn, e.g. more red blood cells, will have diminished a month after returning to sea level, rendering you in much the same shape as before.

Second, prolonged stints at altitude can result in illness, weight loss, immune suppression and sleep disturbances — not exactly conducive to peak performance.

Third, the reduced oxygen availability at altitude dramatically reduces the intensity at which you can train, and reduces the maximal power output you’ve trained so hard to develop.

>>> Review: Altitude Tent and Everest Summit Hypoxic Generator

The fashionable status of altitude training has led to its inevitable commercialisation. Companies now sell altitude training sessions as a shortcut to improved performance, but sporadic and infrequent exposures are unlikely to provide any cumulative effect.

Other products such as elevation training masks are becoming popular, providing resistance to breathing that may help condition the respiratory muscles.

However, the evidence to support the claims being made for these masks is insufficient. Breathing against a resistance doesn’t alter the oxygen content of the air, and so poorly replicates the conditions of high altitude.

I contacted one company manufacturing elevation masks and asked them to clarify their position but received no response.

CW says: For a race at altitude, several weeks of acclimation will boost peak performance, but sporadic or mid-season exposure is unlikely to provide a significant benefit, and may even harm performance.

Therefore, altitude training for amateurs is not usually practical.

Low-carbohydrate diets

Diet regimens have become wildly popular, and most are created by self-proclaimed sports nutritionists eager to carve out a living in the commercial space.

Over the years, athletes have espoused high-protein, high-fat, low-carb, low-GI, intermittent fasting, Atkins, Paleo and Banting. Each of these makes bold claims and is underpinned by fervent ideology.

>>> Find out more: Could cutting carbs help you ride faster?

Assessing the abundant fad diets on the market, a topical review published in the European Journal of Sports Science, showed that moderating carbohydrate intake during training may facilitate important endurance adaptations.

Training activates signalling pathways that promote energy efficiency, but these pathways are also stimulated by low muscle carbohydrate; so, training while moderately depleted can further promote endurance adaptation.

However, the intricacies of scientific research are often overshadowed by sensationalist attention-grabbing headlines in the media. Neglected, in this instance, is that chronic carb restriction can compromise recovery, immune function and performance.

Carb restriction has also been shown to negatively impact on the retention of muscle mass, making low-carb diets inappropriate for strength or power athletes.

Keith Baar and colleagues, authors of the review, state: “As the competitive season approaches, increased training intensity will require fuller glycogen stores.

"Therefore, long-distance [athletes] would be best to intersperse periods of low glycogen training early in their competitive year, shifting to a carbohydrate-rich diet as training intensity increases.”

>>> Should you eat less meat to boost your cycling?

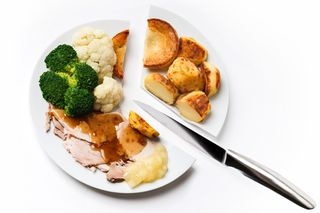

Carbohydrate intake should be carefully managed according to individual training needs, rather than implemented with a generic approach. Far more sensible is carbohydrate moderation rather than elimination.

It’s advisable to speak to an expert because the diet demands walking a tightrope between nutritional success and catastrophe.

CW says: Try safely exploiting the low-carbohydrate state in some sessions with one of the following techniques:

1) train on an empty stomach, ideally before breakfast, because exercising while moderately depleted will stimulate fat-burning pathways

2) avoid eating for a few hours prior to training, stabilising blood glucose levels, to maximise fatty-acid transport

3) avoid carbs for the first hour or two of your session, but take in calories before you become depleted.

Sports supplements

It is believed that the ancient Romans drank the blood of fallen gladiators (as well as urine) for its purported health benefits.

While such practices appear archaic, the mysticism and preposterousness of some of the claims of the sports supplement industry are stark.

According to the Dietary Supplement Education Alliance (2006), the industry is worth around $20bn a year, and is steadily increasing.

Get your post-ride routine nailed

Fat-burners

Fat burning supplements comprise a large proportion of the supplement industry, with L-carnitine (a muscle protein responsible for transporting fat) the most widely sold.

A 2004 review of literature on the effects of carnitine supplementation concluded: “Despite 20 years of research, no compelling evidence exists that carnitine supplementation can improve physical performance in healthy subjects.”

>>> Burn fat on morning rides

It appears, therefore, that the premise alone formed the base for a multi-million pound dietary supplement, despite the overwhelming lack of supporting evidence.

More recent research has finally identified that, under the right conditions, the supplement may indeed increase muscle carnitine concentration, but only when consumed alongside high volumes of carbohydrate in order to spike insulin.

>>> Why stress can make you fat – and what to do about it

For athletes wanting to increase fat metabolism, the process appears counterproductive. There are numerous other commercially available fat-burners on the market, such as conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), caffeine and polyphenol-containing compounds such as green tea extract, but data is inconclusive at best.

CW says: The list of supplements claiming to increase fat metabolism is both substantial and commercially-driven, but the popularity of these products doesn’t reflect their scientific merit, which is severely lacking.

Know your training zones

Carbohydrate supplements

By contrast with fat-burners, the use of carbohydrate drinks/gels is supported by a wealth of evidence. Such is the extent of the positive research on CHO supplements, that it represents a supplement industry in its own right.

The earliest research on carbohydrate supplements goes back as far as 1924 — runners fed sweets in the Boston marathon performed considerably faster than they had the previous year.

>>> Sugar: poison or nectar? Better understanding is needed

A recent systematic review on the evidence of carbohydrate supplements reports that 50 of 61 published studies find positive effects in events of varying duration. In races lasting over two hours, drinking carbohydrate can spare internal carbohydrate (glycogen) and prolong time to fatigue.

>>> Seven simple steps to be a successful cyclist

However, sprint cyclists take note: research has found that the mouth contains glucose receptors that are stimulated when you consume sports drinks.

Simply rinsing with glucose (then spitting it out) can trigger hormonal responses that may reduce perceptions of effort. This may prove useful if you don’t want to guzzle litres of sports drink during a short race. There is little evidence that sports beans and blocks provide a bigger advantage than regular, cheaper sweets.

>>> This is what you have to eat to compete in the Tour de France

CW says: Whether you’re blitzing a time trial or grinding through an ultra-distance sportive, carbohydrate can be a powerful ally. Practise your intake to find out how much your gut can comfortably tolerate.

Ice bathing

After a long, hard gruelling ride there’s nothing worse than plunging your aching, dilapidated lower limbs into freezing water in an attempt to promote recovery. But this is exactly what many of the world’s top riders do.

It may come as a surprise, then, that the practice isn’t supported by much evidence; it might be another futile residual practice that harks back to ancient times.

>>> Prevent muscle pain with good cycling nutrition

Ice bathing gained popularity when it was thought to reduce pain and inflammation. As usual, the science doesn’t prove the benefit.

In a recent report on the entirety of available literature, dating as far back as 1929, scientists found that, compared to several other interventions — including stretching, compression garments and popping a few Ibuprofen — ice bathing led to no reduction in muscle inflammation, and no difference in perception of soreness. It has, at best, a placebo effect.

>>> How gut health affects cycling performance

Several experts — including Dr Chris Bleakley, lead author of the review — suggest the practice should be avoided on grounds of safety: “People shouldn’t underestimate the amount of shock that immersion in cold water can have on the body. It can affect the heart, blood vessels, respiratory system… raise your blood pressure and heart rate.”

CW says: Despite its popularity, ice bathing is unpleasant and ineffective. Instead, perform a cool-down using light movements and stretching, and have a protein and carbohydrate-heavy meal to kick start recovery.

Compression garments

Compression socks and tights are now a common sight around team buses after a stage of the Tour de France. Yet there remains no conclusive evidence that they improve performance.

A 2011 review in Sports Medicine highlighted that there are few, if any, performance-enhancing effects of wearing compression tights during sport, with only isolated instances where tights have been shown to have benefits.

>>> Read more: Could compression clothing benefit your recovery?

Among other reviews published in recent years, there is no firm consensus. There is some evidence that compression tights can increase blood flow post-exercise, thereby helping to reduce muscle swelling, but these effects are also inconsistent.

Given that a majority of the published research has looked at whole-body compression, be cautious of compression-style sports socks.

When challenged for supporting evidence for its claims, one manufacturer directed me to several cherry-picked research papers on lower-body compression; needless to say, the data on compression tights cannot be extrapolated to socks.

Be aware that the minimum pressure required for any observable effect of graduated compression appears to be between 15-30mmHg — the hydrostatic pressure exerted by the water in a swimming pool is substantially greater than that, albeit harder to access after training.

CW says: There is no consistent evidence that compression tights improve performance or reduce injury. If you’re going to be sedentary for many hours after hard exercise, they may help with recovery when compared to normal clothes, but not necessarily when compared to other recovery strategies.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.

-

I'm a mechanic - here's how I keep tubeless setups safe

I'm a mechanic - here's how I keep tubeless setups safeTubeless setups, including hookless, can be safe if you know the pitfalls and take the right precautions

By Joe Baker Published

-

Michelle Froome brands Muslims 'a drain on modern society' in social media tirade

Michelle Froome brands Muslims 'a drain on modern society' in social media tiradeChris Froome's wife and agent says "there are no innocent Gazans" in series of messages on X

By Adam Becket Published