Icons of cycling: Miguel Indurain's Pinarello Espada

The Italian answer to Chris Boardman’s Lotus superbike was Pinarello’s finest hour

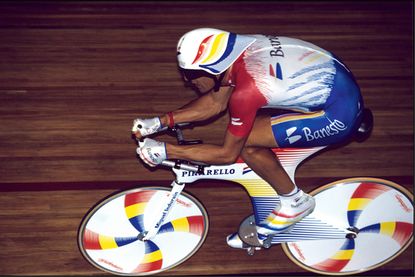

Indurain and the Espada

in full flight on the track. Photo: Graham Watson

The 1990s was the golden era of the aerodynamic carbon monocoque. After the adoption of the material by cycling in the late 1980s, bicycle designers quickly realised they had carte blanche to create whatever shape they found to be most aerodynamic, no matter how outlandish.

At least that was until the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) in 2000 enforced its 1996 Lugano Charter, banning any bike without the traditional diamond-shaped frame.

Buoyed by the reaction to Chris Boardman’s Lotus when he won the Olympic pursuit in 1992, Pinarello set about making its own futuristic carbon monocoque for Miguel Indurain, who was eyeing the Hour Record with a view to reclaiming it for Grand Tour winners from the time trial specialists like Boardman.

Fausto Pinarello told Cycling Weekly when we visited Treviso in 2013: “The Espada was the first time [frame builder and designer] Elvio Borghetto and I had worked with carbon-fibre.

"We did a good job with some people from Lamborghini to make a special design. We had the possibility to go to the wind tunnel and from that time we started to develop technologically more than ever before.”

Before the Pinarello Espada, the challenge for Pinarello was to streamline the hulking Spaniard. “For him the problem was, never change the saddle [position],” said Fausto.

“He was never aerodynamic. We tried to do things with him, but no way. But it was OK because he was strong.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Ready for the record

Finally bike and rider were ready, and on September 2 1994, four weeks after he won his fourth Tour de France, Indurain took the start line at the Velodrome du Lac, Bordeaux.

In his sights, ironically, was an Hour Record that was set on a homemade bike with bearings salvaged from a washing machine.

The machine Indurain had to beat

Icons of cycling: Graeme Obree's Old Faithful

Indurain easily beat Graeme Obree’s distance, becoming the first man to break 53 kilometres. He liked the Espada so much that Pinarello built him a roadgoing version that he used to similarly devastating effect in time trials.

But the reign of Indurain and Espada as Hour Record holders was short lived. Tony Rominger bettered him the very next month, and the month after that Rominger rode an unbelievable 55.291km.

Indurain tried to recapture the record in Colombia at altitude in 1995 but was off the pace from the start.

For Fausto Pinarello, that didn’t matter. Although it didn’t last long at the top, the Espada is still his favourite bike ever.

“You can characterise me as the Espada,” he said. “And Miguel is Pinarello.”

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Simon Smythe is a hugely experienced cycling tech writer, who has been writing for Cycling Weekly since 2003. Until recently he was our senior tech writer. In his cycling career Simon has mostly focused on time trialling with a national medal, a few open wins and his club's 30-mile record in his palmares. These days he spends most of his time testing road bikes, or on a tandem doing the school run with his younger son.

-

Tweets of the week: Brutal weather at Flèche, an idiot sandwich and is there a new POC helmet?

Tweets of the week: Brutal weather at Flèche, an idiot sandwich and is there a new POC helmet?There's a lot of love for Kasia Niewiadoma, and it turns out Norwegians are good in bad weather

By Adam Becket Published

-

Juanpe López wins Tour of the Alps, does 34 kick-ups with a football

Juanpe López wins Tour of the Alps, does 34 kick-ups with a football'My coach said to do it for Betis,' says Spaniard of his boyhood football club

By Tom Davidson Published