Belgian Classics country

Away from the races, the quiet roads of Flanders don't look like much, but it is here that some of the biggest races are won or lost, the reputations of heroes are cemented, and myths and legends are made. Full of history, these are the sites of the most intense, excitement-filled metres in the entire cycling season

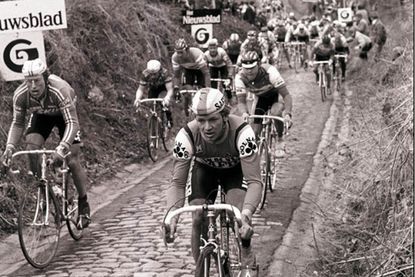

Photo: Graham Watson

From the bergs

In the Tour of Flanders centre just off the main square in Oudenaarde, there’s an exhibit among the sparkling old bikes and faded jerseys that asks what makes a Flandrian. The answer, labelled on an image of a rider grimacing through a faceful of grime, is that they must be hard as nails. A Flandrian is a stoic symbol of strength, built of tough stuff, built for the cobbles. But they are also modest, quiet, and restrained; flamboyancy is well and truly reserved for the Italians.

“Pfff,” says Stijn Vandenbergh as he dismisses Cycle Sport’s suggestion that he’s a local hero. “Maybe.”

Despite the personalised number plate on his sports car, parked outside the Tour of Flanders Centre, Vandenbergh seems a little bit dismayed that he’s recognised around here. That’s what top ten finishes in the Tour of Flanders and Omloop Het Nieuwsblad will do for you. And being 6ft 8in. At least he’s not Tom Boonen, a life size cardboard cut-out of whom adorned the door of a local bed and breakfast.

Vandenbergh is Oudenaarde born and bred: the hospital where he was born is 300m from the finish line of the Tour of Flanders and today his house is on the same street that hosted the finish of his career-affirming first big win, the U23 Het Volk.

His name even means ‘from the berg’. But then the cobbles run through his blood and fire up his turbo-diesel engine. After being introduced to cycling by his aunt, some of Vandenbergh’s very first rides criss-crossed the cobbles with a local club. It was even on the Oude Kwaremont that he won his first club run hill sprint, aged 14.

“I did even more training on the cobbles and the bergs when I was younger than I do now,” he says. “Maybe it was enthusiasm. But I feel fast, and good on the go, on the cobbles.”

The cobbles centre

If anywhere could be called the home of cobbles in cycling, Oudenaarde would be it. The finish of the Tour of Flanders since 2012 and home to the Tour of Flanders Centre, the neat little town is just a stone’s throw away from the decisive cobbles of the race itself. A quick glance at one of the maps bought at the centre and you’re presented with an indecipherable maze of climbs and routes to follow, all within 20km.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Those roads, like the Taaienberg and Steenbeekdries, might form the nail-biting crescendo to the finale of Flanders nowadays, but for 364 days of the year in this part of the world they are just normal roads.

>>> Find out all the latest news on the Cobbled Classics

Every now and again the odd brave car even takes a run up the Koppenberg to get from A to B, although in its case there can be no guarantees it will make it over the top, particularly when the road is buttered with mud from the weekend’s Koppenbergcross race. Indeed here is a hill whose reputation has been cemented by the misfortune suffered on its slopes.

Jesper Skibby was narrowly avoided by an overtaking race commissaire’s car when he plodded his way up the climb at the head of the race in 1987. His bike was not so lucky. After the climb was removed from the race on grounds of safety, it was repaired and reinstated in 2002. In 2009 Fabian Cancellara made a point of walking to the top with his broken chain draped on his shoulders.

Vandenbergh meanwhile, fourth in Flanders last year, is hoping his luck will one day come good; even if it means he’s recognised around town.

“To win I would have to be even stronger than last year, and probably a bit more lucky,” he says. “That can make such a huge difference, just one moment of luck.

“But when you win the Tour of Flanders, it stays with you for the rest of your life.”

Hill country

Not all cobbles have to be gritty and grimy. Take a short trip west of Oudenaarde and you will find yourself in Heuvelland: hill country. There’s a beauty to the cobbled roads here that you don’t find in Flanders or on the road to Roubaix.

The landscape can look just as grim in the gloom of late March when Ghent-Wevelgem passes through the region. But here the bleak farms and their geometric fields are replaced by quaint villages and hamlets sprinkled with small copses and hedgerows.

Cassel, with its winding cobbled roads, is a medieval town perched on a hill looking all the way to the sea and across to the adjacent Mont des Cats, where monks brew abbey beer and make cheese. Everything seems well looked after, the cobbles included.

“They are much better than elsewhere,” explains local ex-professional, Cedric Vasseur. “They are well repaired, without the big gaps in-between the stones.

“They still hit you hard. Physically you still feel like you’re in a washing machine, they hit you. But there aren’t any real traps like in Paris-Roubaix”.

Vasseur has a soft spot for the region. His father Alain won the Four Days of Dunkirk, the region’s stage race that confusingly takes place over five or six days, in 1969. He himself managed a stage win in 2002, but at least has a concrete legacy in the form of the Salle Cedric Vasseur, a sports hall in his hometown of Steenvoorde that was inaugurated after his 1997 Tour de France stage win.

Despite the semi-skimmed cobbles of Cassel and Kemmel, and the pretty little taverns (‘estaminets’) that dot the landscape, the spirit of racing on the cobbles has still infused this bike rider.

“I rode for VC Roubaix for three years before becoming professional. Every training ride we’d start and finish in the Roubaix velodrome,” Vasseur adds.

“When you come from the north of France or Belgium you just aren’t bothered when you come across a sector of cobbles. That’s definitely not the case when you come from the south of Spain or Italy.”

The myth of the Muur

There’s one postman in Belgium who’s more famous than most. Thanks to his local round in the town of Geraardsbergen, he’s been the subject of a short documentary on Belgian national TV. This is because every day he rides his postman’s bike up the Muur van Geraardsbergen, the most famous cobbled road in Belgium.

Such is the position of the Muur in Flanders folklore that when the news erupted that the 2012 Tour of Flanders would be diverted to avoid the Muur in favour of a finish in Oudenaarde, hundreds of cycling fans descended on the cobbled street for a mock funeral, carrying the ‘coffin’ of the Tour of Flanders up to the chapel at the summit. Even today you can still read ‘RIP Tour of Flanders’ daubed in paint on nearby roads.

Once a year the road up to the summit of the Muur was like an alpine climb, boiled down into one kilometre before being rehydrated in Belgian beer. Thousands of fans packed into the broad town square where the climb first heads upwards (at a surprisingly and uncomfortably steep rate) before the Muur proper delves into a deep, claustrophobic cutting that winds its way up to the exposed knoll at the summit, supporting a gravity-defying number of boozy Belgians roaring on their riders.

The Muur, followed by the less difficult final climb of the Bosberg, was more often than not the place where the seeds of victory in Flanders were sown. It was a place where myths and legends were made; think Johan Museeuw bobbing up in the 1990s, or Fabian Cancellara’s 2010 attack that brought allegations he had a motor in his bike.

Three years’ absence has meant a calm has descended on the Muur, along with a thick coating of greasy leaves. In place of Eddy Merckx and Tom Boonen, elderly folk potter around by the fancy cafe at the summit. It is named ‘t Hemelrijck,’ or ‘the Kingdom of Heaven.’ The cobbled climb itself is closed to motor traffic going up, and any traffic going down.

Manmade climb

Whether it was the stubbornness of the landowners around Geraardsbergen, the VIP tent-friendly fields in Kwaremont or the size of Oudenaarde town council’s cheque book, the finale of the Tour of Flanders has now moved west, to the climbs of the Oude Kwaremont and Paterberg.

The Kwaremont was one of the first climbs ever to be introduced into the Tour of Flanders, although in those early days the race went up the parallel main road before it was covered in tarmac.

The Paterberg, however, is a different story; having seen the race and decided he’d like a piece of the action, the local farmer had his steep track up the side of his fields paved with cobblestones and in 1986 the race duly obliged by including it in the parcours.

Nowadays it’s three times up the Kwaremont and Paterberg combo that decides the outcome of the race, with the duo slowly building their own reputation. The Muur, although making cameo appearances in the Eneco Tour and E3-Harelbeke, has departed this world and is now remains just a memory.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Richard Abraham is an award-winning writer, based in New Zealand. He has reported from major sporting events including the Tour de France and Olympic Games, and is also a part-time travel guide who has delivered luxury cycle tours and events across Europe. In 2019 he was awarded Writer of the Year at the PPA Awards.

-

Jumbo-Visma won 3 Grand Tours with 3 different riders in 2023. All of them were wearing these shoes: the Nimbl Ultimate reviewed

Jumbo-Visma won 3 Grand Tours with 3 different riders in 2023. All of them were wearing these shoes: the Nimbl Ultimate reviewedThe Nimbl Ultimate looks fast even when standing still. But how does it fit and perform?

By Tyler Boucher Published

-

'I can not describe my disappointment and frustration': Bora-Hansgrohe rider hits out at non-selection for Giro d’Italia

'I can not describe my disappointment and frustration': Bora-Hansgrohe rider hits out at non-selection for Giro d’ItaliaGerman champion Emanuel Buchmann says he was promised "co-leadership" of Bora team, but he has not been picked

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

Tweets of the week: Cobbles, barbecues, and what on earth is curry ketchup?

Tweets of the week: Cobbles, barbecues, and what on earth is curry ketchup?Strap in for our pre-Paris-Roubaix round-up of social media's finest

By Tom Davidson Published

-

Tadej Pogačar claims Kwaremont-Paterberg Strava KOM in Tour of Flanders romp

Tadej Pogačar claims Kwaremont-Paterberg Strava KOM in Tour of Flanders rompThe two-time Tour de France winner took a host of Strava trophies in Flanders on Sunday

By Tom Davidson Published

-

CW Live: Tour of Flanders updates as Tadej Pogačar and Lotte Kopecky convincingly win; Mathieu van der Poel finishes second; Mads Pedersen beats Wout van Aert to fourth; SD Worx continue dominant spring; Bahrain-Victorious rider apologises for crash;

CW Live: Tour of Flanders updates as Tadej Pogačar and Lotte Kopecky convincingly win; Mathieu van der Poel finishes second; Mads Pedersen beats Wout van Aert to fourth; SD Worx continue dominant spring; Bahrain-Victorious rider apologises for crash;Join us for live updates from the Tour of Flanders as Tadej Pogačar and Lotte Kopecky win the men's and women's editions

By Chris Marshall-Bell Last updated

-

Biniam Girmay eyes Tour of Flanders and Tour de France success in 2023

Biniam Girmay eyes Tour of Flanders and Tour de France success in 2023After becoming first African rider to win Gent-Wevelgem, Girmay plans to take aim at the Tour of Flanders and other monuments next year

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

Tour of Flanders Espoirs cancelled indefinitely

Tour of Flanders Espoirs cancelled indefinitelyThe race's date, location and lack of young riders are all factors in the organiser's decision

By Ryan Dabbs Published

-

E3 Saxo Bank Classic 2021 start list

E3 Saxo Bank Classic 2021 start listList of riders taking part in the 2021 edition of the E3 Saxo Bank Classic in Belgium on Friday, March 26

By Tim Bonville-Ginn Published

-

No fans at Tour of Flanders and other Classics in 2021, according to organisers

No fans at Tour of Flanders and other Classics in 2021, according to organisersThere will be no fans at Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, Ghent-Wevelgem, Dwars Door Vlaanderen, Scheldeprijs or Brabantse Pijl in 2021

By Tim Bonville-Ginn Published

-

Greg Van Avermaet and Patrick Lefevere appear in bizarre new E3 BinckBank poster

Greg Van Avermaet and Patrick Lefevere appear in bizarre new E3 BinckBank posterThe latest poster for E3 BinckBank is another bizarre addition to the catalogue, as Patrick Levefere and Greg Van Avermaet have appeared in fancy dress.

By Alex Ballinger Published