Bradley Wiggins's Tour de France training

A few years ago one of British Cycling's coaches, and now Team Sky's directeur sportifs, Rod Ellingworth, told me about a tick-box list he'd compiled that detailed what was needed to win the Tour de France.

It was made before Team Sky even came into being and it wasn't aimed at any particular rider, just an intellectual exercise, but one that could be used as and when the right rider and the right Tour came along. A lot of the work Wiggins and Sky's Tour de France team have done in Tenerife this year has been to do with making sure those boxes are ticked.

Wiggins went to Tenerife in 2011 after a test following the 2010 Tour showed he tended to de-saturate quickly on climbs above 2,000 metres, which meant the oxygen saturation of his blood dropped suddenly at altitude, basically past the 1,800-2,000 metre mark.

The 2011 camp, just before the 2011 Critérium du Dauphiné, was meant to remedy that problem ready for the high-altitude stages at the 2011 Tour. Wiggins won that Dauphiné with the form of his life, so the same high-altitude camp was chosen to prepare for the Tour 2012.

Why high?

Endurance athletes don't use altitude just for the increased red blood cells, and therefore increased oxygen carrying capacity, that it brings. That was the adaptation they were after many years ago, but now most top coaches regard it almost as a side-effect of altitude, and a fleeting one at that.

The concentration of the hormone responsible for creating red blood cells increases steadily for the first two weeks at altitude then falls to base levels after a month. Also, the post-altitude red blood cells boost only lasts for the life of the cells, about 28 days.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Wiggins and his back-up team are mindful of this. He returned to sea-level on May 26, one week before the Critérium du Dauphiné (June 3-10) to allow for a week for the ‘post-altitude slump', a period when the body readjusts, and for Wiggins to recover from the heavy workload. Team Sky will hold an altitude camp from just after the Dauphiné until June 24, which riders can drop in and out of, and I was told that Wiggins would be there for the duration but I understand he has done some route reconnoitring in France as well.

There are other effects, more lasting effects, that come from sleeping and training at altitude. A few years ago the late Aldo Sassi, a famous Italian coach and the man who guided Cadel Evans to become the formidable Grand Tour racer he is now, spoke to me about altitude training.

"An increase in the number of blood capillaries in the lungs and muscles is a big and lasting adaptation. More capillaries means more oxygen can be picked up by the lungs and more delivered to working muscles. The body also becomes better at taking up, transporting and delivering oxygen. There are hormonal changes too, mostly to do with the testosterone to cortisol balance in the body which maintain and even build muscle. That's a valuable thing during a hard training camp," he said.

And Sassi also pointed out: "Athletes use their lungs fully, breathing deeper and using a greater proportion of the places in them where oxygen is absorbed by blood, which concentrates in the bottom of the lungs. It forces them to breath deeper and more efficiently, and it conditions the muscles involved in breathing. There are also some changes of muscle enzymes that are of lasting benefit to performance," he said.

Any genuine Tour de France contender has to be able to deal with high mountains

Wiggins's programme

Wiggins and Team Sky followed a similar programme in Tenerife to one Evans has done, riding down Mount Teide to do sea-level training, mixing in quality sessions on the many other slopes Tenerife has to offer, and climbing back up the big mountain, where the roads reach 2,100 metres, to get the benefits of some hypoxic training.

The sleep-high, train-low model is the best of both worlds. Athletes gain the positive benefits by sleeping at altitude while avoiding the negatives of altitude by training at lower levels. The negatives are loss of muscular power and increased stress on the body if it's constantly working at altitude.

British Cycling's chief coach, Shane Sutton says: "A stage racer needs to put in the hours to get the stamina and build slowly. Then he needs training sessions that push up his anaerobic threshold, and sessions that stretch the time he can stay at that threshold."

That's what Wiggins has done. Starting last November he did a lot of low-intensity work to build a base. Then he worked on his threshold by doing long climbs at a power output calculated to push him towards his optimum power at threshold, which is the factor that puts a racer in the ballpark for winning the Tour. And while this was going on Wiggins had to become as lean as possible.

A Tour winner needs to get close to a threshold power output of 6.7 watts per kilogram of body weight.

Do that and he will be at the front in the mountains, which is crucial. When Wiggins won the 2011 National 10-mile title he said his average power output was 476 watts, which because 10s are ridden at slightly above threshold meant his threshold then would have been around 460 watts. This tallies with what Sutton told me in 2009 when he put Wiggins's threshold at between 440 and 460. Wiggins weighed around 70 kilograms going into the 2011 Tour, which gave a watts per kilo of 6.57.

Throughout April and May this year Wiggins did long climbs working at the power calculated to push him towards his optimum threshold, until he was doing sessions like three repetitions of 25-minute climbs in 35 degrees of heat. The idea was to build up to doing simulated Tour de France stages - that's 4,000 metres of climbing in a six-hour ride - and doing them back to back.

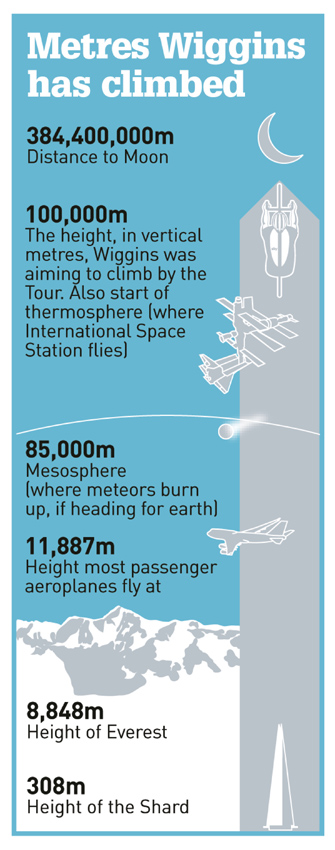

In all, Wiggins aimed for 100,000 metres of climbing to build his threshold and hone his climbing power, and since he was already good at time trials, the effects were clear when he dominated the Dauphiné.

Eradicating weaknesses

But climbing and time trialling are just two boxes, albeit big ones, ticked. They are the boxes that make a Tour contender, but there are others that make a Tour winner, and the most important of those is the ability to make and withstand searing attacks in the mountains. And it's an area where Wiggins has been suspect in the past.

Wiggins sprints in the saddle to stay close to Cadel Evans and Chris Froome on La Planche des Belles Filles

To address this Wiggins, who says he hates training in a gym, trained as a track racer during the winter of 2010/11. Pursuiters - and let's not forget Wiggins was the best before his conversion to the road - have high anaerobic thresholds and can produce power anaerobically as well. They also do this at high pedal cadences, which is the best way to climb. If these abilities can be adapted to the road, theoretically they should produce a good climber. And doing full-on track starts builds cycling-specific muscles that will help road racers accelerate in an attack.

We don't know how successful his approach would have been because Wiggins crashed out of the 2011 Tour, breaking his collarbone, but he struggled on the notorious gradients of the Angliru in the 2012 Tour of Spain, although that was mainly due to the fact he was overgeared and just back from his Tour injury.

So Wiggins went back to the gym this winter and did a strength and conditioning programme building the muscles in his core that cycling can't reach, to the depth he needed. He also did specific bike training, like high-intensity intervals with varying rest, designed to help him mount powerful anaerobic attacks and recover from them, and cope when others make them, which is crucial.

The signs are that it has worked. Wiggins won a Tour of Romandy stage in a sprint, and there is no better test of pure power than sprinting, and he had no trouble at all on the very steep Joux-Plane in the Dauphiné.

Steep climbs are a feature of the 2012 Tour, and Wiggins's biggest rival, Cadel Evans, is good at them. Has Wiggins ticked the last box? We will know for certain on stage seven, on the steep new finish of La Planche des Belles Filles, when the battle to win the 2012 Tour de France really starts.

Go get some altitude

You don't have to go to Tenerife - why not try Putney? The Altitude Centre in Putney offers courses of hypoxic training in an altitude chamber, or you can hire equipment to do hypoxic training at home or a tent to sleep in and do the whole sleep high, train low protocol.

Elite and weekend-warrior athletes use their services, as Richard Pullen from centre explained, when we had a look at their facilities in 2011: "Anyone can benefit but we recommend two one-hour sessions for a minimum of three weeks before changes will take place."

The price for an hour in the hypoxic chamber is less than you might pay for a personal trainer, and equipment can be hired. Have a look at www.thealtitudecentre.com. If you've got the best bike, and you've done the training and are looking for an extra two or three per cent, which could win you a race or cut your time in a sportive, the altitude centre is worth considering.

This article first appeared in the June 28 edition of Cycling Weekly magazine. Available every week for £2.85 from WHSmiths and all good newsagents. Digital versions also available via Zino and as an iPad app via iTunes.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast