11 revolutionary road bikes that changed the world of cycling

We take a look at 11 bikes that changed the sport of cycling and the way we think about bike design

Throughout the ages, riders equipment has always to evolved so, we take a look at the most iconic and game-changing road bikes throughout the ages. This list is by no means exhaustive, but contains some very famous and innovative machines.

1. Legnano Team Bike (1948)

Ridden by: Gino Bartali

In 1940 Campagnolo invented the Cambio Corsa derailleur. Before this, riders had to remove their rear wheel and flip it around to change gear. Giving them a choice of two! Italian great Gino Bartali was one of the first riders to use it, giving him a bit of an advantage in the mountains.

The gear is changed by operating by two levers on the right side of the bike’s right seatstay. The top lever releases the rear wheel, and the lever below it operates a simple guide that moves the chain from one sprocket to the next. The video below shows it in action.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AIZhSNdO_Zo

The chain shifter is on the top portion of the chain, above the chainstay, meaning it is necessary to back pedal if you want to change gear. Once the gear change is made, the riders weight moves the wheel back and re-tensions the chain. Despite its simplicity, for its time, the Cambio Corsa was a masterpiece of engineering.

2. TI-Raleigh Pro Team bike (1980)

Ridden by: Joop Zoetemelk

Raleigh set up a pro road team in 1972 with the express intention of winning the Tour de France. Under the brutally professional leadership of Peter Post, Ti-Raleigh became the most effective team in bike racing, winning nearly everything, with Joop Zoetemelk delivering a yellow jersey to the iconic Nottingham brand in 1980. To this day Raleigh is still the only British bike ever to have won the Tour.

The bikes were built in Raleigh's Special Bike Development Unit (SBDU) where a team of experts under the direction Gerald O'Donovan were dedicated to making the best race bikes in the world. Using Reynolds 531 tubing, Post wanted the best, so the bikes were fitted with Campagnolo Record. Wheels were hand-built in house and the frames were sprayed and assembled in Ilkeston.

Raleigh have an impressive palmarès: One Tour de France, 62 Tour stages, 26 Classics wins and six world titles.

3. Look KG86 Tour de France (1986)

Ridden by: La Vie Claire

Carbon fibre is the bike material of choice in the 21st century, at least so far. Some manufacturers experimented with carbon frames in the early 1970s, but although its strength to weight ratio was ideal for bike frames, it proved difficult to use in practical situations.

Look were the first company to produce a useable frame with carbon tubes designed for cycle racing. The tubes were made by a French company TVT, who combined Kevlar with layers of woven carbon fibre. The tubes were bonded into aluminium lugs in a way reminiscent of the first use of aluminium tubes in cycling.

Look's KG86 was the first production frame, and it received an immediate boost when Greg LeMond won the Tour on it. TVT also made frames under its own name. Peugeot and Vitus made similar frames.

4. Vitus 979 (1987)

Ridden by: Sean Kelly

Aluminium bikes grew in popularity in the pro peloton during the early 1970s, although Jaques Anquetil first tried an aluminium frame in the 1960s. Aluminium is lighter than steel and very strong, but in the early days it made for a very flexible bike frame.

The French company Vitus persisted with aluminium, and by the mid-1980s it was producing frames using 979 Dural tubes. Duraluminium, to give it its full name, was an aluminium alloy that was light and a lot stiffer than the old frames.

The tubes were still bonded, but they were butted into lugs, and design tweaks like a one-piece head tube and lug unit increased frame stiffness. They were also anodised, not painted, which made a shiny scratch resistant finish on the frames. They were good enough for Sean Kelly who won a load of races on the Vitus 979.

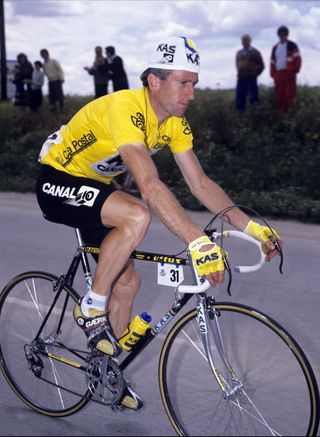

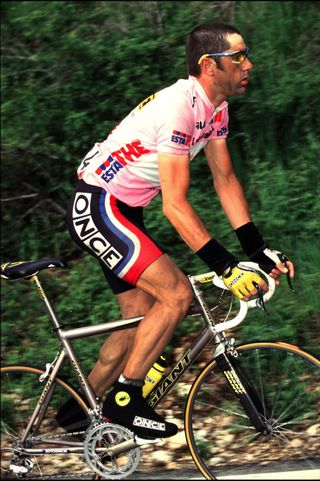

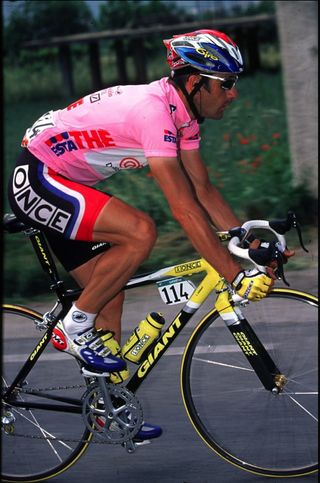

5. ONCE Giant-TCR (1999)

Ridden by: Laurent Jalabert

The Giant TCR, as ridden by the ONCE team during the late 1990s, was the first mass produced frame with a sloping top tube and compact geometry. The design, by British innovator Mike Burrows, involved a smaller, more compact frame than had gone before. Not only was it stiffer, lighter and used less material, but it could also be made to fit more people in fewer factory sizes.

Another British frame maker, David Lloyd, had introduced a frame with a sloping top tube even earlier, the 'Concept 90', which he produced from 1990 onwards. However this was made of steel, to the TCR's aluminium.

Laurent Jalabert was one of a number of top pros to ride the TCR and also use the frame in conjunction with smaller 650c wheels over the standard 700c diameter. This was popular on stages that finished with a climb, with some pros convinced that bikes with slightly smaller wheels were faster. The idea didn't catch on, but in certain circumstances it may have had advantages.

6. Trek OCLV (1999-2005)

Ridden by: Lance Armstrong

Trek owes Lance Armstrong a lot (even now), at least in terms of the brand exposure. It always made good, well thought-out bikes, the work of enthusiasts who understand how bikes work, but when Armstrong "won" his first Tour de France in 1999, this relatively new American company received world wide publicity.

When Armstrong returned to racing with the US Postal team in 1998, Trek was using the team to push its OCLV carbon bikes. OCLV stands for Optimum Compaction Low Void, which is to do with the way the carbon fibre layers are laminated in their frames. The process was carried out in house in Waterloo, Wisconisn and matched the aircraft industry standards for carbon fibre.

Armstrong won the 1999 Tour on a Trek OCLV 5200 and it quickly became one of the fastest selling bikes in the USA. It was also the first ever tour victory for Shimano, despite the fact it made its debut in 1973 with the Belgian Flandria team.

7. Cervélo Soloist (2001)

Ridden by: CSC team

In 2003 the CSC Team began using Cervélo as their bike sponsor and adopted the Canadian brand's Soloist as their bike of choice. Team CSC were crowned the world’s number pro cycling team while riding Cervélo for three years. The partnership lasted for six years, until the end of 2008.

The Soloist was iconic, firstly by being one of very few aluminium frames that achieved success against carbon fibre road bicycles, but also for its ground breaking aerodynamics. Cervélo claim that it was first aero-road bike, setting a trend that continues to this day in future bike design. At the time of release, the aero-foil shaped down tube and seat post were revolutionary.

8. Suspension LeMond (1993)

Ridden by: Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle

The Pinarello K8-S used by Team Sky was far form the first road bike to feature shock absorbers. The first mountain bikes didn't have suspension, but once suspension forks had been developed some road teams thought that they might be useful for the cobbled Classics. RockShox made a limited run of road forks to give the idea a go. Maybe it would catch on?

They didn't hurt on the cobbles. In fact, Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle won Paris-Roubaix in 1992 and 1993 riding on a pair of RockShox, and for a while a number of pavé specialists used them.

The forks were lighter than the mountain bike forks and had a lockout switch on the handle bars. Bianchi and Cannondale experimented with other designs, but they didn't catch on. Soon the pros abandoned bikes with suspension and returned to the old standard of cushioning; double wrapped bar tape.

9. Cannondale CAAD3 (1997)

Ridden by: Mario Cipollini

Mario Cipollini didn't contribute much to cycling technology, but he did a lot for cycling style. His flagrant disregard for the rules led to the colourful team kit you see today, and particularly the way the yellow, green and polka dot jersey wearers can coordinate their kit.

The outfit he chose for the Tour stage on July 4, 1997 - a Saeco team jersey, stars and striped shorts and a stars and striped bike from his American sponsor Cannondale saw him fined, for something which is common practice today. Note the four-spoke Spinergy wheels which were eventually banned by the UCI, after the spokes were deemed too dangerous.

The other iconic feature of Cipollini's bike was the stem. Regardless of the bike he rode or team he raced for, irrespective of geometry, Cipollini always raced on a 13cm stem set as low as it could go. In fact his handlebars were so low on some bikes he could hardly ride in drops, which is why you will occasionally see pictures of him sprinting on the hoods. If Cipollini couldn't do something in style he didn't do it at all.

10. Specialized McLaren S-Works Venge (2011-2016)

Ridden by: Mark Cavendish

Specialized showed real marketing flair when it launched the Venge with Mark Cavendish as its front man. At the time, he was the undisputed fastest sprinter in the world. Specialized worked with F1 team McLaren to develop the Venge, with 30 years of experience in composites and a lifetime of thinking about aerodynamics, this was a good choice.

The designers had to come up with an aerodynamic frame without adding weight or compromising handling. The project achieved this with special design tweaks, like a one piece bottom bracket and chain stay unit, and by adding material only where it was needed. The bike also features a very substantial Zipp stem designed to cope with huge stress Cavendish creates.

The image of Cavendish sprinting to victory down the Champs-Élysées is certainly iconic and will live long in people's memory.

11. Trek Madone SLR 6 Disc (2018)

Ridden by: Trek-Segafredo

Aero bikes have come some way since the early days, which could date back to Cannondale’s aluminium bikes in the 1990s. You’ll be hard pressed to find a company that doesn’t offer an aero machine in its range and they don’t come much slipperier than the Trek Madone, which is used in competition by WorldTour squad Trek-Segafredo.

Our in house testing actually found the Madone to be one of the fastest out there and it has since been updated to include discs.

What makes this bike game changing is that it's lightweight – around 1000g for a 56cm frameset - compliant and aerodynamic. Trek has done this by including its ISOSpeed technology to offer up over 17 per cent more compliance than its previous version, without changing ride characteristics or affecting drag. The adjuster will allow you to make the rear end 21 per cent stiffer if needed too.It has discs too, so stopping power is excellent.

So the Trek Madone Disc and others around this bracket now offer up more than just an aerodynamic bike but a fast all-round bike you can use everyday.

They are closer to GC bikes in terms of weight and ride quality whilst being more efficient and that certainly is a game changer as technology still develops.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Oliver Bridgewood - no, Doctor Oliver Bridgewood - is a PhD Chemist who discovered a love of cycling. He enjoys racing time trials, hill climbs, road races and criteriums. During his time at Cycling Weekly, he worked predominantly within the tech team, also utilising his science background to produce insightful fitness articles, before moving to an entirely video-focused role heading up the Cycling Weekly YouTube channel, where his feature-length documentary 'Project 49' was his crowning glory.

-

Top 5 five U.S. cities with the most bike commuters revealed

Top 5 five U.S. cities with the most bike commuters revealedAccording to new research from DesignRush, Corvallis, Oregon, has the highest percentage of workers that regularly commute to work by bike.

By Kristin Jenny Published

-

ENVE Composites under new ownership: private Utah investment firm takes the wheel

ENVE Composites under new ownership: private Utah investment firm takes the wheelAmer Sports, the parent company of Enve Composites, announced today that the Enve brand has been acquired by PV3, a Utah-based private investment firm allegedly owned by avid cyclists.

By Anne-Marije Rook Published